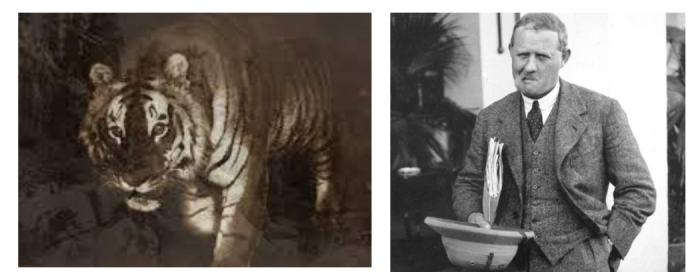

The first image of a tiger in the wild was taken in India by Frederick Walter Champion, a pioneering preservationist and former soldier in the British Indian Army. He was also an officer in the Imperial Forestry Service (Indian Forest Service). Jim Corbett regarded him as a creator of the camera trapping method as well as a pioneer of nature photography in India.

Speaking of Corbett, Champion’s unwavering dedication to conservation motivated him to trade up his gun for a camera, and the two joined forces to found India’s first national park, founded in 1935 and later known as Corbett National Park.

Champion, born on August 24, 1893, in Surrey, England, was raised in a household of outdoor enthusiasts by his entomologist father, George Charles Champion. Later, a taxonomy of the forest types in India was credited to his brother, the forester Sir Harry George Champion. In contrast to other officers of his period, he disliked the idea of killing animals for sport and chose to capture images of them through nature photography.

Champion had already attempted to capture a photo of a tiger in its natural setting before joining the IFS. It took him 8 long years to capture these photographs, as wildlife researcher Raza Kazmi highlighted in a Twitter thread. These photos, which were taken in the Kumaon forests, were first featured under the heading “A Triumph of Big Game Photography: The First Photographs of Tigers in the Natural Haunts” on the front page of “The Illustrated London News” on October 3, 1925.

He published a book titled “With Camera in Tiger-Land” two years later. The publication of “photographs of wild animals just as they survive their daily lives in the great Indian forests, away from every hand of man,” as opposed to photographs showing these magnificent creatures fleeing from beaters or about to be shot by hunters, this book established new standards for the publication of wildlife images.

The effects of this strategy have been extensive. This method has been improved and is now referred to as “camera trap photography.” Conservationists still use this technique to count tigers and track their whereabouts.

In his preface to “Tripwire for a Tiger, Selected Works of FW Champion,” renowned tiger specialist K Ullas Karanth provided the following backdrop for how challenging this procedure was for the Champion.

“I marvelled at Champion’s dedication with his old-fashioned camera traps, 60 years earlier, while I toiled with my camera traps in the late 1980s, photographing tigers to gain a more exact count using 35mm SLR cameras and tripwires. I was shocked to find from his descriptions that Fred Champion only managed to capture nine high-quality pictures of tigers in 30 years of deploying camera traps in prime tiger habitats.

Legacy as conservationist

Champion was not only known as the “Father of Camera Trap Photography,” but he was also instrumental in advancing the topic of animal conservation at a period when British politicians took great pride in big game hunting. He assigned “shooting zones where there were expected to be no tigers for shooters to shoot” because he was worried about the tigers’ declining numbers due to hunting, according to Rangarajan. He fervently supported restrictions on gun licenses, the entry of motor vehicles into protected forests, and the reduction of cash awards for wildlife slaughter.

For instance, the shooting ranges of the governor-general were located in the Shivaliks, where Champion had served with actual distinction. Corbett would arrange significant game shots for top British Indian federal officials before he came across Champion’s works, such as “With a Camera in Tiger-Land” (1927) and “Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow” (1934).

Speaking of other species, his book “The Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow” discusses the Indian jungles he visited, including the pangolin, honey badger, swamp deer, and scaly ant-eaters, in addition to the tiger-like honey badger. He would later get some of the earliest images of wild leopards, sloth bears, dholes, etc., at night.

He died in 1970 at 76, leaving behind a tremendous legacy. He was a pioneer who pushed India to have a robust forest department. He thought they were obliged to safeguard wild animals like the tiger and their natural habitats.

As Champion put it, “Such images, hanging on one’s walls in following years, bring back starkly, as no skin or head can ever do, what may have been the most exhilarating moments of one’s life.”

If one half-closes their eyes while looking at the photos, they will undoubtedly appear to be genuine scenes.